Police, Fire and Ambulance Dispatcher

Summary

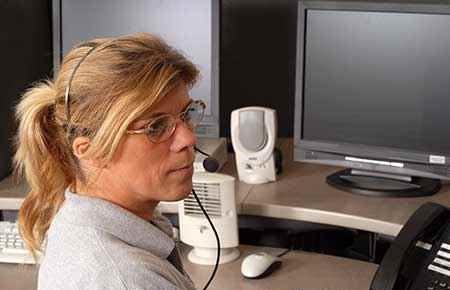

Police, fire, and ambulance dispatchers, also called public safety telecommunicators, answer emergency and nonemergency calls.

What they do

Police, fire, and ambulance dispatchers typically do the following:

- Answer 9-1-1 emergency telephone and alarm system calls

- Determine the type of emergency and its location and decide the appropriate response on the basis of agency procedures

- Relay information to the appropriate first-responder agency

- Coordinate the dispatch of emergency response personnel to accident scenes

- Give basic over-the-phone medical instructions before emergency personnel arrive

- Monitor and track the status of police, fire, and ambulance units

- Synchronize responses with other area communication centers

- Keep detailed records of calls

Dispatchers answer calls from people who need help from police, firefighters, emergency services, or a combination of the three. They take emergency, nonemergency, and alarm system calls.

Dispatchers must stay calm while collecting vital information from callers to determine the severity of a situation and the location of those who need help. They then communicate this information to the appropriate first-responder agencies.

Dispatchers keep detailed records of the calls that they answer. They use computers to log important facts, such as the nature of the incident and the caller’s name and location. Most computer systems detect the location of cell phones and landline phones automatically.

Dispatchers often must instruct callers on what to do before responders arrive. Many dispatchers are trained to offer medical help over the phone. For example, they might help the caller provide first aid at the scene until emergency medical services arrive. At other times they may advise callers on how to remain safe while waiting for assistance.

Work Environment

Dispatchers typically work in communication centers, often called public safety answering points (PSAPs). Some dispatchers work for unified communication centers, where they answer calls for all types of emergency services, while others may work specifically for police or fire departments.

Work as a dispatcher can be stressful. Dispatchers often work long shifts, take many calls, and deal with troubling situations. Some calls require them to assist people who are in life-threatening situations, and the pressure to respond quickly and calmly can be demanding.

Most dispatchers work 8- to 12-hour shifts, but some agencies require even longer ones. Overtime is common in this occupation.

Because emergencies can happen at any time, dispatchers are required to work some shifts during evenings, weekends, and holidays.

How to become a Police, Fire and/or Ambulance Dispatcher

Most police, fire, and ambulance dispatchers have a high school diploma. Many states and localities require dispatchers to have training and certification.

In addition, candidates must pass a written exam and a typing test. In some instances, applicants may need to pass a background check, lie detector and drug tests, and tests for hearing and vision.

Some jobs require a driver’s license, and experience using computers and in customer service can be helpful. The ability to speak Spanish is also desirable in this occupation.

Most dispatchers are required to have a high school diploma.

Training requirements vary by state. The Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials (APCO International) provides a list of states requiring training and certification.

Some states require 40 or more hours of initial training, and some require continuing education every 2 to 3 years. Other states do not mandate any specific training, leaving individual localities and agencies to structure their own requirements and conduct their own courses.

Some agencies have their own programs for certifying dispatchers; others use training from a professional association. The Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials (APCO International), the National Emergency Number Association (NENA), and the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch (IAED) have established a number of recommended standards and best practices that agencies often use as a guideline for their own training programs.

Training is usually conducted in a classroom and on the job, and may be followed by a probationary period of about 1 year. However, the period may vary by agency, as there is no national standard governing training or probation.

Training covers a wide variety of topics, such as local geography, agency protocols, and standard procedures. Dispatchers are also taught how to use specialized equipment, such as two-way radios and computer-aided dispatch software. Computer systems that dispatchers use consist of several monitors that display call information, maps, any relevant criminal history, and video, depending on the location of the incident. Dispatchers often receive specialized training to prepare for high-risk incidents, such as child abductions and suicidal callers.

Many states require dispatchers to be certified. The Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials (APCO) provides a list of states requiring training and certification. One certification is the Emergency Medical Dispatcher (EMD) certification, which enables dispatchers to give medical assistance over the phone.

Dispatchers may choose to pursue additional certifications, such as the National Emergency Number Association’s Emergency Number Professional (ENP) certification or APCO’s Registered Public-Safety Leader (RPL) certification, which demonstrate their leadership skills and knowledge of the profession.

Pay

The median annual wage for police, fire, and ambulance dispatchers was $41,910 in May 2019. The median wage is the wage at which half the workers in an occupation earned more than that amount and half earned less. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $27,190, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $64,950.

Job Outlook

Employment of police, fire, and ambulance dispatchers is projected to grow 6 percent from 2019 to 2029, faster than the average for all occupations.

Although state and local government budget constraints may limit the number of dispatchers hired in the coming decade, population growth and the commensurate increase in 9-1-1 call volume is expected to increase the employment of dispatchers.

Similar Job Titles

911 Dispatcher, Communications Officer, Communications Operator, Communications Specialist, Communications Supervisor, Dispatcher, Emergency Communications Operator (ECO), Police Dispatcher, Public Safety Dispatcher, Telecommunicator

Related Occupations

Licensing Examiner and Inspector, Radio Operator, Gaming Surveillance Officer and Gaming Investigator, Interviewer (except Eligibility and Loan), Dispatcher (except Police, Fire and Ambulance)

More Information

The trade associations listed below represent organizations made up of people (members) who work and promote advancement in the field. Members are very interested in telling others about their work and about careers in those areas. As well, trade associations provide opportunities for organizational networking and learning more about the field’s trends and directions.

- American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO

- APCO International

- Fraternal Order of Police

- IAFF FireFighters

- International Academies of Emergency Dispatch

- NENA: The 9-1-1 Association

Magazines and Publications

- Journal of Emergency Dispatch

- Police Chief Magazine

- Journal of Emergency Medical Services (JEMS)

- Fire Rescue Magazine

Dispatchers keep freight, work crews, and equipment moving along the vast network of transit lines across the country and around the globe. Dispatchers send workers and service vehicles out to make installations, service calls, or emergency repairs. They set schedules for moving freight and equipment and keep in close contact with work site personnel to adjust schedules as needed. Dispatchers generally relay work orders and information to workers and field personnel using phones or 2-way radios. They track work progress, and record customer requests, expenses, charges, and inventory, and make reports as needed. They also keep work crews informed about delays caused by hazards such as road construction or poor weather conditions. Most dispatchers work in the trucking industry, taxi and limousine services, building equipment contractors, freight and rail transportation, or local messenger services. Schedules of 40 hours or more in a week are common in this field. A high school diploma or equivalent is typically required.

Content retrieved from: US Bureau of Labor Statistics-OOH www.bls.gov/ooh,

CareerOneStop www.careeronestop.org, O*Net Online www.onetonline.org